A new book containing the work of Robert Doisneau brings us a much wider perspective on his life and photography beyond the world-famous kiss, says Damien Demolder

I wonder how I’d feel if I had an archive of 450,000 pictures that represented my heart and soul as a candid street photographer, and the one I was best known for was a staged shot I did with some actors for a commission. That the one picture was quite at odds with the photography closest to my aims and intentions might make my head hurt. Anyone old enough to have walked passed an Athena store in the 1980s or anyone given to admiring the framed art on sale at the local garden centre will be familiar with the image ‘Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville’ – Kiss by the City Hall – by Robert Doisneau. It is an iconic image, and one that gave generations of teenagers a bedroom-wall portal to the fantasy of Parisian romance.

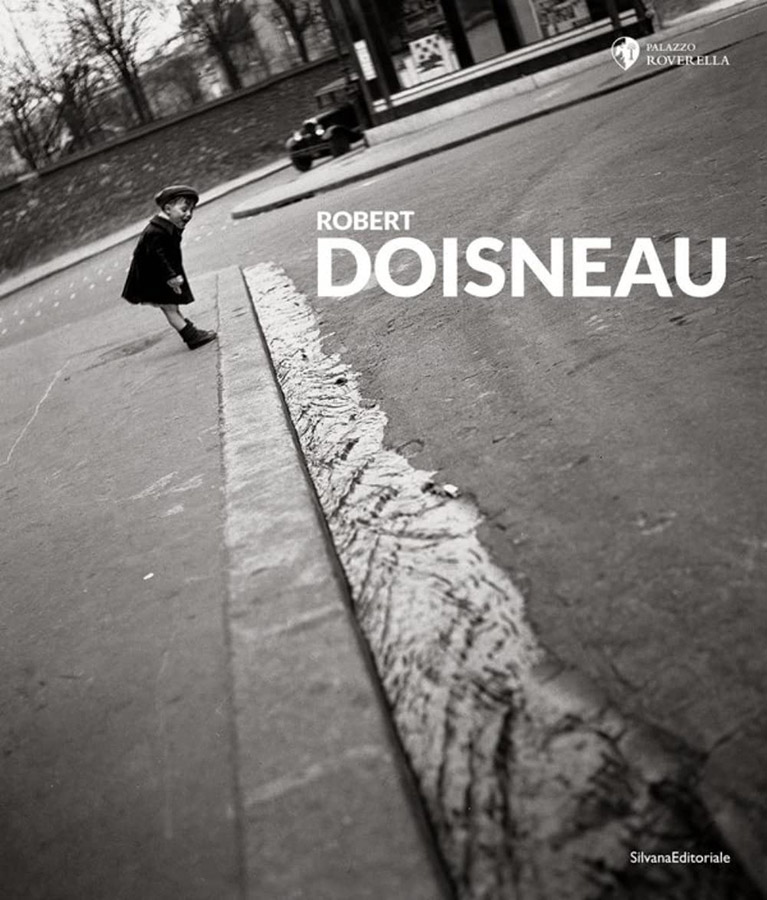

It earned M Doisneau a few francs too, but it seems that didn’t take the edge off the court cases it created, firstly with a couple who thought they were in the picture, and finally with the actress who actually is in the picture. That is said to have rather ruined the final years of Doisneau’s life. Doisneau however was about very much more than this one picture, as a new book called Robert Doisneau shows us. Of course the famous picture is included, but it rests well beyond the half-way point, by which stage we have been given plenty of opportunity to form opinions of the work he loved most.

Indoors to out

Doisneau started his photographic life in the studio of a graphics house, before moving on to work as a studio assistant and then as an industrial photographer for the car maker Renault. It was only after five years photographing ‘people who get up early’ that he was fired for being late and became a freelance photojournalist with the Rapho Agency – and got to take the more journalistic and documentary pictures he enjoyed.

What has survived of his work, and forms the subject of this book, is his street photography, his portraiture and his atmospheric, moving, positive and beautifully taken pictures of life in the towns and cities of France. The book shows us a bit of his industrial work at the start, and near the back we see five pictures of the thousands he must have shot when he worked at Vogue – but he wasn’t interested in either subject matter.

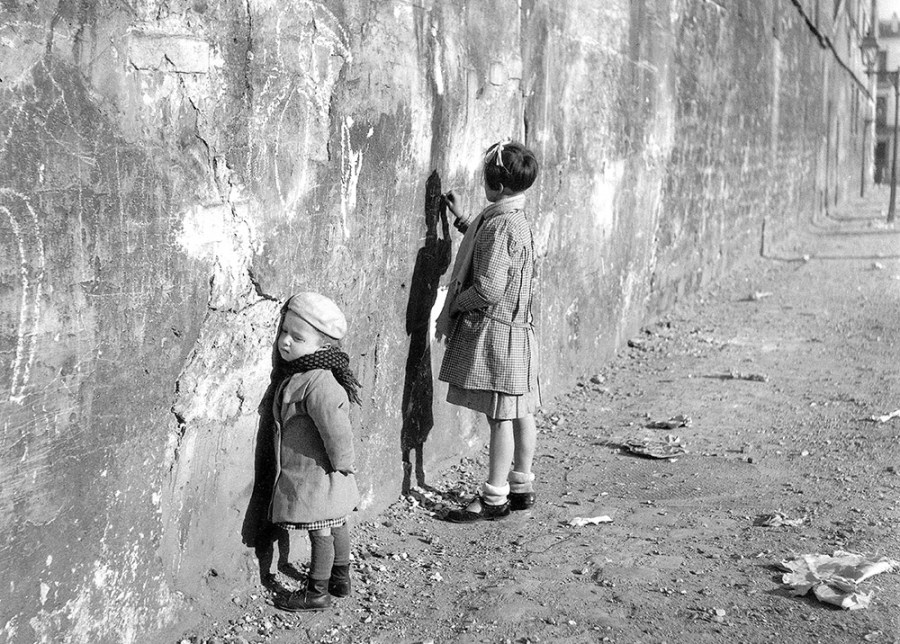

Where he came alive and where he produced the most stunning images was out in the streets observing the world and the people in it. Remarkably he was a shy person and nervous of being seen taking pictures of strangers. The distance and his hidden status comes across in some of his work – but not in much of it. He preferred to shoot with a Rolleiflex TTL camera that he could look down into so he wouldn’t be looking at his subjects as he photographed them, and no doubt the almost silent click of the shutter would have been inaudible in the racket of expressive French conversation in the streets, cafes and bars he worked in.

Unlike the Magnum members of the time, who required that the rebate of their negatives be printed around their pictures to prove the composition was all in-camera, Doisneau happily crops his square 6x6cm frame to all sorts of oblongs according to the requirements of the scene. This book shows few square pictures, considering most of his work was shot square during the 1930-60s period with which this book deals.

This only shows his priorities were at odds with the well-known photographers of the day. Doisneau was great friends with Cartier-Bresson – whose portrait of Doisneau graces the first pages – but that friendship didn’t convince him to take up Cartier-Bresson’s invitation to join Magnum.

What comes across in this book is that Doisneau didn’t take himself too seriously. There are lots of serious subjects covered, but there is also a lot of fun and joy in his pictures. It’s clear that he likes people and photographs them for the love of humanity rather than with the somewhat sneering, superior approach that other photographers can adopt. He celebrates life and how others choose to spend theirs.

Doisneau is quoted as having said ‘The world that I tried to show was a world in which I could feel at ease, where people would be nice, where I would find the kindness that I wished to experience. My photos were a kind of proof that this world can exist.’ And that mission is well illustrated in these pages. The pictures are not of drama, conflict, sadness or misery. In many ways these are easier things to photograph and report on, but Doisneau chooses to look on the bright side, to find scenes where people are enjoying themselves. The pages brighten our day instead of weighing us down.

Visual value

It is easy to get carried away when looking at old pictures, and to be swayed into believing they are good just because they are old. There are many pictures taken yesterday that were they taken today would not get a second look. Doisneau’s pictures, at least those in this book, stand the test of time and are all still fabulous to look at. They may have got better with time, I don’t know, as now they carry a historical perspective on top of their intrinsic social and visual value.

I think what has made the pictures last so well is that the subjects Doisneau chose to shoot, and the way he chose to shoot them, appeal to our basic humanity. They are of the things we will always find interesting. He does show us everyday life, but not all of everyday life. He picks the bits that will make us smile, feel happy and will uplift us.

This is what makes his pictures universally appealing. They are little moments when the juxtaposition of elements and people come together to create an amusing episode – something of note in what would normally be the unremarkable. They are, indeed, decisive moments.

His compositions all have great physical depth, and he controls our eye from foreground to the distance without us even realising. He rarely shoots straight on, and uses disappearing and converging lines to show us the subject of his focus and the environment in which he found it. He has a genius for timing, for knowing what will happen next and a keen eye for displays of human behaviour.

‘People like my photos because they see in them what they would see if they stopped rushing about and took the time to enjoy the city,’ he is said to have remarked, and it is true. Normal people rush around the streets with their head occupied by their own life; Doisneau hangs around with his head occupied by what everyone else is doing. He said knowing how to wait was a key skill a photographer must master – standing still, observing and anticipating the moment the scene will come to fruition, when the investment will pay off.

One-to-one

There is a section near the end of the book, before the Vogue images, that shows Doisneau’s portraiture. While being in a room with someone for the agreed purpose of taking their picture is a very different situation to the passing happenstance of the street, there is a powerful connection between these portraits and the rest of the work in the book.

The portraits are a mix of the formal and the casual, but all offer us an intimate connection with some part of the subject’s character. They are photographed without effect or technique to get in the way of us seeing. The images have a naturalism that allows us to be a part of the scene. We aren’t left to admire the person from a distance, but feel we are there in the room.

Feel-good glow

This is a most enjoyable book, and one that has collected a sample of Doisneau’s work that shows some of his breadth while emphasising what he enjoyed most – and what he was best at. We get a sense of the man behind the camera, and a feel-good glow from his love of the world around him and of humanity in the towns and cities of France in this period.

There’s a definable and consistent style that runs from one page to the next, and in each image there is as much for the layman to delight in as there is for the photography student to learn. As cheesy as ‘Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville’ has become through over-use, and as shocked as the world was when we found out it was staged, it is still a first-class picture, and very much in Doisneau’s style – that’s why we like it so much. He was clearly a great master of photography and our life and work can only improve by looking at his.

Robert Doisneau is published by Silvana Editoriale, RRP £25. ISBN: 9788836649747.

Further reading:

Is it a bird or is it a plane? Capturing Dod Miller’s Birdmen

The untold story of Vivian Maier

Ed Kashi: 40 years of abandoned moments

Fake news: how Jonas Bendiksen hoodwinked the photographic community with The Book of Veles