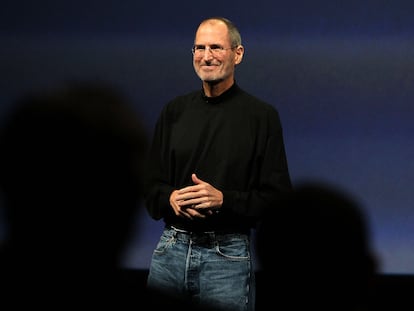

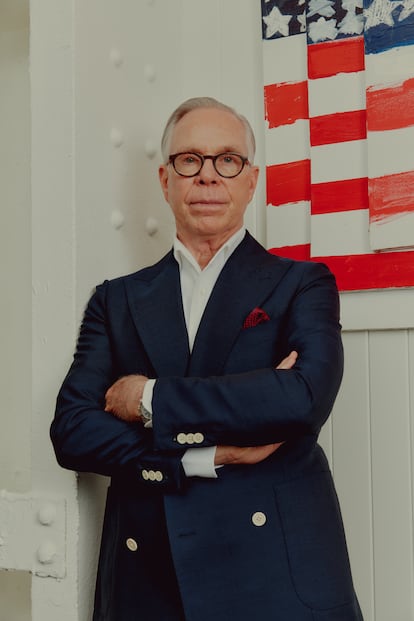

Tommy Hilfiger: ‘Our fans are going to be living in the metaverse. Many of them are living in it now’

The veteran American designer has been focused on two ideas for nearly four decades: creating timeless fashion and connecting with younger audiences. At 71 years old, he has just made the leap into the digital environment that fuses physical and virtual reality

A framed poster hangs in the hall of the headquarters on Madison Avenue, New York. It reads “The four great American designers” above a series of initials left for the viewer’s interpretation: Ralph Lauren, Perry Ellis, Calvin Klein and, obviously, Tommy Hilfiger. In 1985, no one knew the New York designer, who had just founded his eponymous brand with the help of Indian businessman Mohan Murjani. The campaign displayed in kiosks and telephone booths in the Big Apple ensured that, in a matter of months, the designer was on everyone’s lips. Who the hell is Tommy Hilfiger? “Because before I started the brand, I started stores called People’s Place, connecting fashion and music. My store was all about the people who were into fashion or music. I always try to involve real people in everything,” he reflects today from his office.

That store, which had a hair salon and a concert hall in the basement, and which he founded with $150 and a handful of second-hand clothes, ended up going bankrupt in 1977. Over the next seven years, Tommy Hilfiger designed for other brands. He studied business and temporarily moved to India to learn first-hand how the business of manufacturing and exporting denim garments worked. When he met Murjani, the owner of the Gloria Vanderbilt product lines, it was clear to him that he wanted to make “fashion for everyone’s needs.”

Forty years have passed since then. Hilfiger, now 71, is about to present a fashion show at a drive-in theater in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The collection mixes physical garments with digital ones. What you see on the catwalk are sold to dress up avatars on Roblox, one of the main platforms in the metaverse. “Our community, our fans, are going to be living in the metaverse, and many of them are living in it now, but it’s just going to expand greater and greater worldwide,” he adds.

According to Morgan Stanley, by 2030, virtual fashion is expected to generate more than €50 billion ($48 billion) in turnover. This year, almost all major brands have invested in plots in simulated reality worlds such as Roblox and Decentraland. Hilfiger’s first foray was in 2021, when he launched his collections of skins – avatar clothes – and later Tommy Play, an interactive game based on his universe. In 2020, he created Team Tommy, an initiative that supports the talent and visibility of gamers. “A lot of it came from video games, and it has morphed into NFTs, Web3, digital skins, avatars and we want to be ahead of the game,” he explains. “As a company, we’ve been studying it, we’ve been immersing ourselves in it, and we feel that our relationship with Roblox is very powerful and important,” he explains.

The designer is obsessed with being connected to the needs and dynamics of the present. Yet for many, Tommy Hilfiger is synonymous with preppy style, the aesthetic traditionally associated with privileged white Americans. Hilfiger grew up in a middle-class community in a small province of upstate New York. As a teenager, he worked as a clerk in a clothing store on Cape Cod, and he was drawn to striped polo shirts, chinos, baseball jackets and loafers. But, as he himself says, “classics can be modern.”

In the 1980s, Ralph Lauren triumphed by cashing in on the public’s aspirations of belonging to an Ivy League fraternity, even if only in appearance. Hilfiger, well into the decade, played on this idea with cultural references that had little to do with that world. Along the way, he brought former Ralph Lauren executives into his company. In 1997, he became a tour sponsor for The Who singer Roger Daltrey. He also sponsored the tours of Lenny Kravitz, Sheryl Crow, Jennifer Lopez and Britney Spears – who had just released Baby One More Time – and he chose the late R&B singer Aaliyah as a brand ambassador. Dressing this type of character with an aesthetic so far removed from their lifestyle, was an effective way of breaking down prejudices and, of course, attracting attention: “I’ve always been diverse. I’ve always had diversity within the teams, the campaigns, models,” he says. “People and brands are just now getting it. It took a long time, but it’s happening.”

In fact, the key to Tommy Hilfiger’s long-standing success may be that it is not considered a fashion brand in the strict sense. It is not interested in elitist catwalks: its shows, in different cities around the world, are more like massive interactive events. Hilfiger is not interested in the inbreeding typical of the fashion world, which recycles the same personalities. His portfolio of ambassadors includes global stars such as Zendaya and Lewis Hamilton, but also semi-unknown figures such as Big Zuu and Mr. Brainwash. Perhaps more importantly, he is not interested in associating himself with a specific audience: the broader, the better. “Fashion is not the final thing,” he explains. “I’ve always connected the brand to the pop culture, mainly through music, but also through art, entertainment, Hollywood, celebrities, sports stars.” He learned that from his friend Andy Warhol, to whom he has dedicated this latest collection, Tommy Factory, which is named after the artist’s famous New York studio.

Hilfiger met Warhol when he founded his brand, in 1985. His investor, Mohan Murjani, introduced them. “He was working with Stephen Sprouse on a fashion line, he was all about the culture, and it was a magnet in bringing the people from the fashion world, the music world, the art world, the entertainment world, all together. He saw the value in celebrating those types and immersing himself in pop culture. So I was inspired by that,” he explains. Hilfiger, who today wears a pristine suit jacket, experienced the peak of 1980s New York. His work includes constant references to Basquiat, Keith Haring and CBGB. But he does not feel nostalgic. “Nostalgia is boring,” he says. For him, pop means bringing together Bob Colacello, the legendary editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine; drag queen idol Lady Bunny, the biggest celebrity icons (Gigi Hadid, Travis Barker), and unknown figures, from tattoo artists to street artists, all in the one show. “We feel that an experiential show is much more important than just a normal fashion. Normal fashion is a bit boring,” he says. “I would rather not do it than to do something that we’ve done in the past that is not relevant for today.”

When things have gone wrong for Tommy, he has not had any qualms about rebuilding himself with typically Warholian ideas. Such conceits are not usually well regarded in this industry, but they have worked well for him. When sales declined around the turn of the century, he signed an exclusive contract with Macy’s. Later, he took in TV reality shows, going on to host his own show, Tommy Hilfiger Presents: Ironic Iconic America. When his fame took off, he sold the company in 2010 to the German investing firm PVH, which also owns Calvin Klein, for €30 billion. Since then, according to company data, the brand has grown between 15% and 30% per year. He guides the entire process, sometimes making risky decisions.

Six years ago, he became the first designer to implement the “see now, buy now” system in his fashion shows – that is, to put the clothes on sale immediately after they appeared on the catwalk (the usual waiting time is six months). “Nobody understood it,” he concedes. Two years ago, Tommy Hilfiger became the first major brand to design adaptive clothing for people with disabilities. Three of his seven children are autistic. “It came to me as an idea because of my family,” he says. “I looked around and found that nobody else was doing it. So we decided to do it. It has worked out very well. We started with children and then went to adults, and now everybody wants it.”

In 2016, Hilfiger published a memoir that made it to The New York Times bestsellers list. Entitled American Dreamer, it presented the designer as yet another great example of the American dream, a discourse that complements the preppy aesthetic and American ethos that he has always flaunted. The discourse may be familiar, but among today’s fashion trends, there is nothing that Tommy Hilfiger hasn’t already done. Racial diversity? Two programs supporting designers belonging to racial minorities and a podcast about forgotten African-American designers. Sustainability? Two circularity and water-saving projects, and the mission to be completely clean by 2030. Equal opportunities? A four-year program that finances social entrepreneurs and a firm commitment to emerging design, both in terms of resources and visibility. The latest beneficiary was Richard Quinn, the 31-year-old British man whose dramatic fashion captivated Queen Elizabeth II in 2018 and who designed part of the new Hilfiger collection. “He was wearing our tartan plaid shirts during his school days. I think that we did a great job in coming together, both of us, figuring out how to balance his look with our look, with a real line, a collection that is true fashion.” Because if there is something Tommy Hilfiger does with fashion, 40 years on, it’s to have fun: “True fashion has to be fun. Doing something boring makes no sense.”