Guy Taplin: Driftwood sculptures by Essex artist sell for thousands

- Published

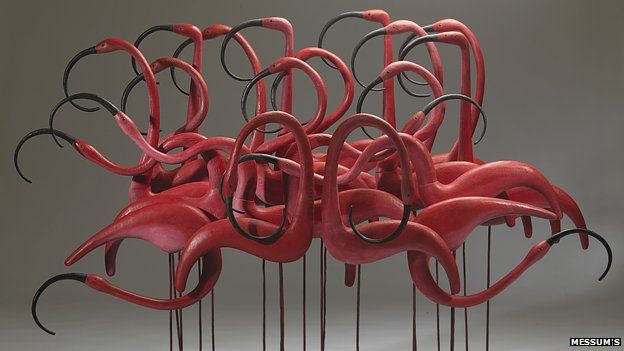

Driftwood found on the Essex coast and transformed into avian sculptures by an untrained artist, is selling for thousands of pounds to a growing fan base of celebrity collectors.

Guy Taplin, 73, from Wivenhoe, spends hours collecting natural materials during a daily pilgrimage along the shoreline near his studio, looking for inspiration from the birdlife among the "transitory" nature of the tides and objects with a history.

His work also now features household items that were used to "pack" Seawick beach, near Clacton-on-Sea, after it was damaged during the floods of 1953. "It's all being eroded away now so things just appear," he said.

"I found what must have been a drain plug out of a sink, it was copper, beautifully green with holes in and like a time-capsule."

Born an east end cockney in 1939 and describing himself as a "barrow-boy at heart", Taplin has worked as an artist for more than 30 years following an eclectic career.

Previous jobs have included military service, selling fashion on London's Carnaby Street during the swinging '60s and working as a bird keeper in Regent's Park while training to become a Buddhist monk.

His latest collection of work, featuring more than 60 pieces, goes on show at London's Messum's gallery on 6 February - it is expected to sell for about £500,000.

'Passionate and obsessed'

"The birds are, for me, a key to entering an environment which is just pleasurable and birds are something that everyone knows just a little bit about," he said.

"I've never regarded myself as a real artist, I'm a bit basic I guess. I like my work to be fun and that you don't have to know a lot about art to enjoy it.

"The galleries make it very special, but I don't like that fancy stuff. If the work works - it works."

Taplin's love affair with birds started as a young boy, inspired during a country walk in Hereford with his mother.

"I found a hedge sparrow's nest, I must have been about three and it had bright blue eggs in it. I thought 'this is fantastic' and I think this was the turning point," he said.

The emerging artist then turned his passion for wildlife into sculpture while working in London's Regent's Park.

"I used to look after the ducks in the park and saw all these decoy ducks in the antique markets. I thought 'I could make some of these' - somebody came into the park and asked if they could have a few and it took off," he said.

"I must have had something that really appealed to people that I couldn't see, but what it boiled down to was that I was incredibly passionate and obsessed with making these wooden birds."

Taplin's early birds sold for £15. His sculptural pieces, a blend of found materials and wood bought for the work, now command fees of more than £30,000.

Wood needs 'life'

He said: "It depends on what effect I want, the Scarlet Ibis are all made from red cedar because I want a uniformed look. A piece like that might take a couple of months from end to end, maybe a little bit longer.

"I look for good bits of wood and pieces that can augment the birds that I place upon it.

"The base is driftwood, frequently in blue or grey with old nails in it, and it's important to me this wood has history - it's no good to have a boring old bit of wood, you need something that's had a bit of life to it.

"In the case of the Essex coast it might have been part of a caravan or chalet at Jaywick or Leewick.

"I've always been tied into the past and how important it is to us now. It's like a river flowing and you have to jump into it."

Despite turning 74 in a few weeks time Taplin has no intention of stopping.

"To be honest, other than saying it's because I want to - I don't know why I do it, but you need to keep a spark alive. Stopping would be a form of death - it would be the end of the road," he said.

- Published31 January 2013

- Published31 January 2013

- Published23 August 2012

- Published4 July 2012